“The most basic needs of our community are not being met, we are back to square one.”

A Brief History

The Great Depression

Homelessness first grew to a level of national concern in the U.S. during the Great Depression. Unemployment raged and shanty towns sprung up across the country.

1970's

In the 70's, federal failures to address poverty and the inability of state and local governments to supply affordable housing amidst the growing cost of living gave rise to another significant period of homelessness in our nation's history. Reduced federal and anti-poverty poverty programs, destruction of low income housing and single residency occupancy hotels (SROs), and deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill all contributed to a rise in homelessness.

Current Factors

- Approximately one third of homeless adults suffer from severe mental illness

- Approximately one fifth of homeless adults are veterans

- The issue of long term affordable housing is still ignored

- Short term shelter provision, initially meant to be one element of a three party strategy for reducing homelessness, remains the primary policy of local government and non-profits

Veterans

Many veterans are homeless due to conditions like PTSD, drug abuse, traumatic brain injury (TBI), depression, and anxiety. Often veterans return home and try to transition back to civilian life, but within three years become homeless.

Former U.S. Army Medical Service Officer, Shad Meshad, who served in Vietnam in 1970, pioneered treatment techniques for what would later become known as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

TENT CITIES

As income disparity grows in the Bay Area, homeless encampments are growing larger.

Photos by Grendelkhan and Shannon Badiee from Wikimedia Commons

The Jungle

San Jose, California

An estimated 4,000 homeless people live in San Jose and 7,400 in Santa Clara County. Approximately 500 are living in their vehicles. One solution from the City of San Jose is to provide safe parking lots where people can stay in their cars and get access to housing resources and long term services.

Unlike San Francisco, where tent encampments are easily spotted under freeway overpasses and on sidewalks, San Jose’s homeless often stay out of sight on the city’s 140 miles of trails, creeks, and riverbeds.

"The Jungle" is a 65-acre area bordering Coyote Creek in San Jose and was once the largest homeless encampment in the U.S. The makeshift village was home to as many as 300 people.

Direct discharge of human waste into streams was deemed unacceptable by the regional Water Quality Control Board. The surrounding community was concerned that the planned closing of the Jungle would disperse homeless people into neighborhoods. In early 2015, the city closed the Jungle and undertook a vegetation and wildlife restoration project, planting willows, maples and sycamores.

However, some feel that the larger problem has been overlooked. Robert Aguirre, a homeless activist, says, “I’m much more interested in repairing the people than the creek. Don’t get me wrong, both are important. But people should come first, and now they’ve just been scattered all around the city.”

Some have petitioned for legal camping areas for the homeless instead of evicting them from location to location.

Cisco's $50 Million Pledge

In March 2018, Cisco pledged $50 million to fight Silicon Valley Homelessness. San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo commended Cisco CEO Chuck Robbins for his contribution. The homelessness crisis, Liccardo said, is the “moral imperative of our generation."

"In Silicon Valley, we have all of the problem and all of the solution in the same 20-mile radius,” Loving said. “We have people who can solve homelessness, and companies that can help solve homelessness, along with thousands of people who slept outside last night."

Solutions

"Communities must help those without their own effective networks to knit together the pieces of a stable and purposeful life."

Currently, many government and "not for profit" services are not directly linked, so an individual can go through the cycle of entering a hospital or treatment facility, receive treatment, then be discharged back to the street only to go though the same process again within months.

"Supportive Housing" that provides access to health, mental health, employment and other services often costs less than having people drift between shelters, emergency rooms, and jails from one institution to another.

Housing First Approach

- Provide a stable permanent home FIRST that offers support

- Many homeless programs insist on preconditions such as sobriety or psychiatric care and moving through transitional housing before being able to be eligible for permanent housing

The Six

Skid Row Housing Trust is a non-profit developer that serves LA’s homeless population. The Trust believes that the environment plays a vital role in residents’ recovery. Good design is treated as a basic civil right. They currently house 1,800 people per year. Skid Row Housing Trust aims to provide spaces that: 1) Promote positive social interaction; 2) Feel Safe; 3) Provide Dignity; and, 4) Help gain greater acceptance for the homeless community into the larger community.

The Six is a 52-unit complex designed by Brooks + Scarpa that provides affordable housing to homeless veterans. Completed in 2017, the Six features a green roof, a bicycle storage and workshop area, a public patio, and an edible garden. The building's public courtyard is lifted above the street by one level, which provides a pedestrian-oriented street edge and visual connection/physical separation for tenants.

“We share a sense of responsibility to the city and the community to do our best to enhance the built environment”

ADUs

Providing incentives for homeowners to build Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) is one solution that may help alleviate the housing shortage.

In 2017, L.A. County launched a pilot program to help house the homeless. They offered residents up to $75,000 to build an ADU on their property for a homeless family or individual. The County will streamline the permitting process for those who participate in the program. While rent and utility cost will be up to the homeowner and tenants.

For this solution to work, homeowners would need to develop a willingness to share their space with others – essentially opening up their homes to strangers. In a society where we are so used to having our own private spaces, this is an obstacle that may be difficult to overcome.

CitySpaces MicroPAD

At the same time as boasting the highest unprecedented prosperity of any metropolitan area in the country, San Francisco is also home to about 6,700 homeless people. Local developer Panoramic Interests introduced the MicroPAD for CITYSPACES supportive housing project to address San Francisco's homelessness crisis. The modular 160 square-foot units include a private bathroom and kitchenette, cost about half as much as a conventional housing unit, and can be fabricated in just four weeks.

Photo Credit: Panoramic Interests

Photo Credit: Panoramic Interests

Photo Credit: Panoramic Interests

While neighboring cities Berkeley and Oakland approved initiatives in early 2017 to develop compact modular units to help house their homeless residents, the city of San Francisco has yet to move forward with any such plans. Meanwhile, Panoramic Interests is looking for private sites to construct a MicroPAD development in San Francisco, with the aim of leasing the entire site to the City after installation.

FCA Projects

Sobering Center

San Jose, California

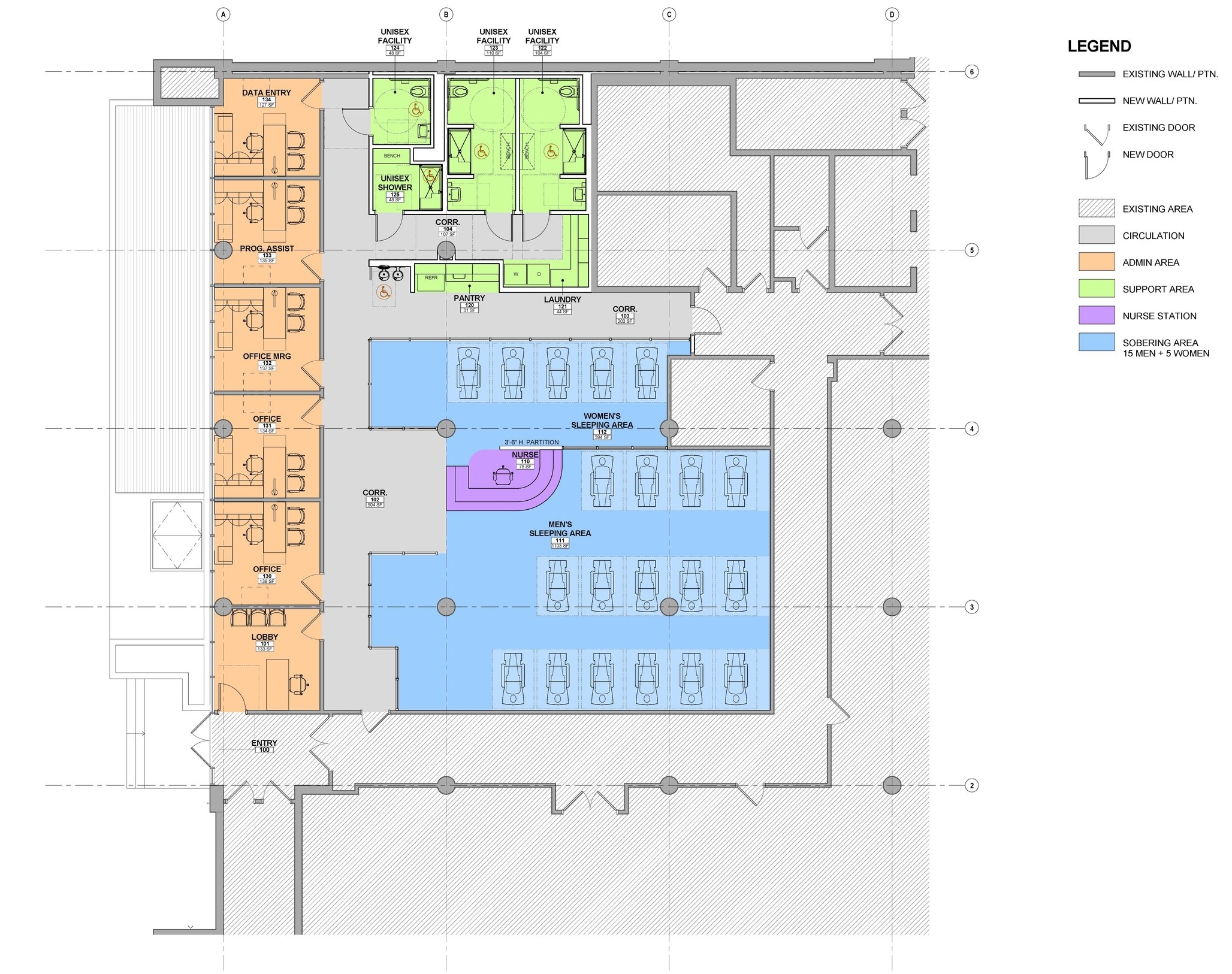

Fong & Chan Architects was commissioned by the County of Santa Clara to design the Sobering Center, located at 151 W. Mission Street in San Jose, California. The project involves the renovation of approximately 3,800 square feet within the existing Re-entry Resource Center Building in order to establish a permanent Sobering Center. The Sobering Center’s purpose is to provide specialized healthcare services for individuals with chronic alcoholism that are in need of stabilization services. As an alternative to sending intoxicated individuals to jail, they can be brought to the Sobering Center to sober up and receive care.

The program includes private staff offices, single occupancy unisex toilet and shower facilities, laundry and pantry areas, and a sobering station. Within the sobering station, there are two distinct zones: one zone for men which contains fifteen recliner chairs, and another smaller zone for women which contains five recliner chairs. The two zones are separated by a central nurse station which allows both zones to be visually monitored from the nurse station while maintaining visual privacy between the two zones.